Pope Pius XII played a key role in removing the socialist Benito Mussolini from power in Italy

The conspiracy that overthrew and imprisoned Benito Mussolini in 1943 had been orchestrated by the Vatican many years earlier. Marshal Pietro Badoglio, who was Chief of the General Staff of the Kingdom of Italy, had vigorously opposed the attack on Greece in November 1940. He was a determined adversary of the dictators Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Through the contact at the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, Ludwig Müller (who was the channel through which the German resistance communicated with the Vatican) learned that Mussolini was circulating a petition among Italian officers demanding a court-martial for Badoglio. Mussolini’s maneuver incited Badoglio to get in touch with the German resistance. As Müller reported: “I believed—I must choose my words carefully—that we could do business with Badoglio.” Badoglio declared himself ready to overthrow Mussolini, provided that the Pope and the King would support him. Müller brokered a liaison agreement between the German and Italian resistance movements that if one side carried out the coup, the other should follow suit immediately afterward.

For nearly two years, Badoglio delayed the coup. He hoped the German resistance would act first. Finally, in November 1942, the U.S. invasion of North Africa forced him to take initiative. At that point, with the Allies less than 150 kilometers from the Sicilian coast, Mussolini’s position had become precarious. On November 24, Badoglio sent Princess Maria José of Savoy to discuss regime change with Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, Pope Pius XII’s assistant. “I will report,” replied the prelate, and he informed the Pope of the interview with Princess Maria José, asking permission to continue the contacts. The words of Pius XII are not known, but it is certain that he gave a favorable response, because Monsignor Montini and the Princess met again, and the prelate reported from inside the Vatican that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s special envoy to the Pope, Myron Taylor, had guaranteed that the United States would welcome Italy’s exit from the war.

However, the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, a distinctly anticlerical figure, learned of the plot and vetoed the Vatican’s involvement, exclaiming: “No priests,” and exiled the Princess to the hermitage of Sant’Anna. Almost at the same time, Wilhelm Canaris met Müller at the Hotel Regina in Munich, and after a surreal dinner with Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Canaris suggested to Müller that he try to arrange a face-to-face meeting with Badoglio. One month later, on December 21, Badoglio secretly sent his nephew to meet with the Cardinal Secretary of State of the Holy See, Luigi Maglione, seeking the Pope’s blessing for the approach regarding the conspiracy with the King of Italy to overthrow Mussolini.

Through these intrigues, Allied diplomats began negotiating a peace agreement with Badoglio. As Müller recalled:

“At the end of 1942, I received news—not from Leiber, but from someone within the Vatican circle—that a prominent Italian figure had presented a peace proposal, a suggestion or inquiry regarding the terms of a separate peace with Italy. The response to the inquiry, I believe from Washington and not from London, was: 1) Italian concession of its North African colonies. 2) Pantelleria (an Italian island near Tunisia) to go to England. 3) An offer concerning the Italian evacuation of Albania. 4) [This was exciting for us, in a certain sense. The gist was approximately this:] Italian Tyrol was to become part of a new German state in the South.

This worried not only us (in Canaris’s circle), but also—as Leiber informed me—him as well. He struck his head with his hand, as Germany’s participation with the Allies greatly conflicted with our earlier discussions with England. I asked Leiber to try to find out from his contacts how the idea was viewed in the United States—whether they fundamentally disagreed with it or thought along the same lines as the British.”

One month later, Pius XII had the elements of Badoglio’s conspiracy in his hands. While Roosevelt was publicly advising Italy to leave the Axis, Taylor, his personal representative to the Pope, was conducting a parallel secret operation with Pius XII.

“You will recall your constant contact with His Holiness via Vatican Radio from Washington,” Taylor later reminded Roosevelt. “The first preparation for Mussolini’s downfall was the day I brought you a secret message, in response to one I had authored regarding Mussolini’s fall and Italy’s exit from the war, which you described as the first rupture in the entire Axis structure, and which reached me through that papal channel.”

The Vatican’s preparations for Mussolini’s removal began on May 12.

Maglione summoned Italy’s ambassador to the Holy See, Count Galeazzo Ciano, and delivered an oral communication. The Pope suffered for Italy and with Italy, Maglione stated, and would do everything possible to help the country. Therefore, the Pope intended to let Mussolini know his thoughts, though avoiding direct intervention. However, as Father Peter Gumpel, a Vatican expert on Pius XII, later said with a laugh:

“Of course, that’s just a discreet way of saying: ‘Can I be of any help as a mediator?’”

Reading between the lines, Ciano abruptly replied, “Well, the Duce will not seek that.”

Mussolini promised to fight, but Pius XII had opened a channel for further discussions.

On May 20, Pius XII wrote to Roosevelt, asking him not to bomb Italian cities. Although he did not say so explicitly, the Pope considered the bombings by both the Allies and the Axis to be acts of terrorism, as they killed women and children in London and Berlin for political rather than military reasons. However, the Pope’s letter revealed his deeper strategy—he asked Roosevelt to have mercy on Italy in future peace talks, indicating that the Vatican was expecting an Allied victory.

Prudently, Pius XII positioned himself between two opposing sides, to which he posed the same question: “How can I help?”

Even though Pius XII worked with Roosevelt to remove Mussolini, the Vatican maintained that the Pope had not been an active conspirator.

“We must be very careful when speaking about involvement or direct influence,” Father Gumpel later stated. “For it is not the Vatican’s role to interfere in the affairs of foreign states. Its style is very discreet. It is more diplomatic and acts more prudently to avoid exposure to serious accusations.”

The Lateran Treaty prohibited the Vatican from intervening in foreign policy.

How would Hitler have reacted if Italy had left the war through a papal intrigue?

"The Holy Father is of the opinion that something must be done," recorded Monsignor Domenico Tardini, his aide, after receiving an encrypted American message regarding the regime change. "He cannot refuse to intervene, but he must do so with the utmost secrecy."

On June 11, Pius XII received important political information: through an informant, he learned that Victor Emmanuel III had secretly met with two former non-fascist Italian politicians.

The fact that even the King—a notorious procrastinator—recognized the need to act suggested that the status quo would soon begin to crumble. Six days later, the Apostolic Nuncio to Italy visited the King and warned him that the Americans would show no mercy unless Rome withdrew from the war.

Pius XII had top-level intelligence—directly from Roosevelt—regarding what was to come. Yet, the King remained uncertain about what to do.

A month later, on July 10, the Allies invaded Sicily. Three German divisions fled to the Italian Peninsula, indicating the immediate possibility that Allied troops would follow them. This prospect exasperated not only the Italian people but also Pius XII. Neither he nor his aides Maglione, Montini, and Tardini had wanted Italy to enter the war, and now they were working hard to get Italy out of it.

Pius XII managed to be informed about the legal measures of the Grand Council of Fascism against Mussolini. On July 18, Cardinal Celso Costantini wrote in his diary:

"Italy is on the edge of the abyss."

The next day, when Rome was bombed, fate had already been sealed. Italy had lost the war, and its leaders crossed the secret bridge that Pius XII had built toward peace.

Six days later, the King had Mussolini arrested and appointed Badoglio to govern in his place. Pius XII made no public statement, but an American diplomat observed that he did not seem at all unhappy.

He spent the following month as the secret host of negotiations between Badoglio and the Allies, which led to an armistice on September 8.

Hitler swore to invade the Vatican two hours after learning of Mussolini’s downfall.

Albrecht von Kessel stated that Hitler blamed Pius XII for Mussolini’s removal because the Pope had been speaking with Roosevelt over the phone for a long time.

REFERENCE

Mark Riebling, O Papa contra Hitler, pp. 184-186. S. Bertoldi. “Umberto e Maria Josè di Savoia”, Milano 1999 pp. 123-129

0

RT

RT

Styxhexenhammer666

Styxhexenhammer666

Richie From Boston

Richie From Boston

Sant77

Sant77

AwakenWithJP

AwakenWithJP

TheSaltyCracker

TheSaltyCracker

Nick J Fuentes

Nick J Fuentes

KnowMoreNews

KnowMoreNews

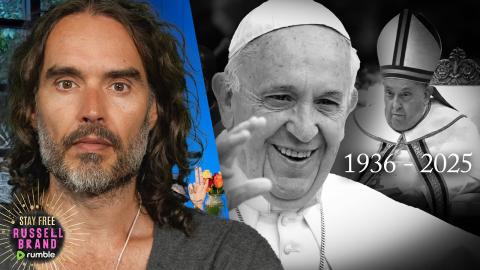

Russell Brand

Russell Brand

Redacted News

Redacted News

Doggk

Doggk

TheQuartering

TheQuartering

X22 Report

X22 Report

JudgeNapolitano

JudgeNapolitano

Log in to comment